Ivy | Connected Talent Management at Amazon

As the head of UX Research and Design for Amazon’s Global Talent Management Organization, I lead my team to conduct the research, design the strategy, and deliver the first version of Amazon’s Talent Management system, Ivy.

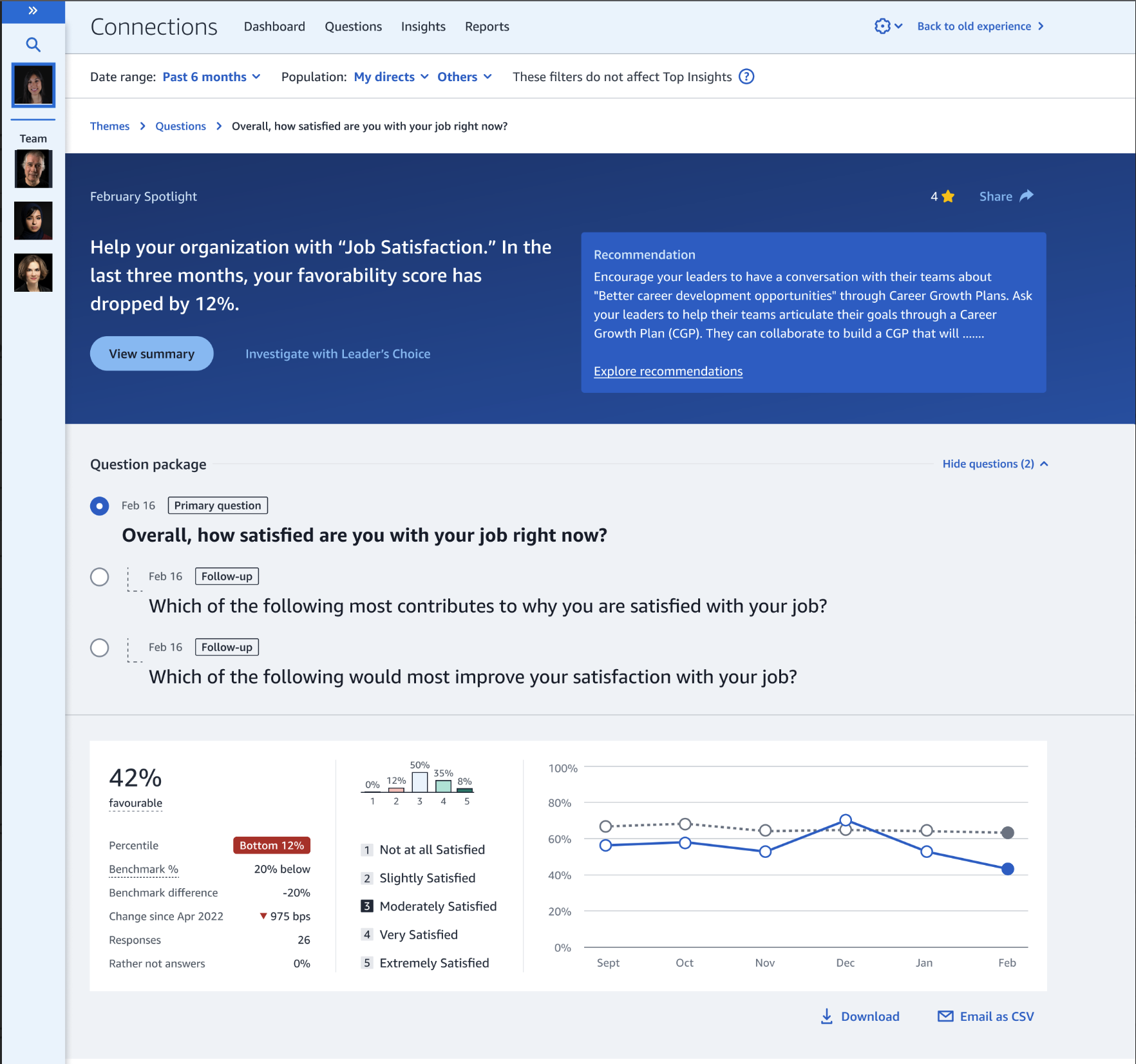

Ivy is the way employees, managers, and senior leaders experience talent management at Amazon, from hiring, pre-boarding, and onboarding processes to career development, feedback, talent evaluation, compensation, promotions, and underperformance. By consolidating experiences into a single product, Ivy, employees and managers understand how employees grow at Amazon and managers can make the highest value talent decisions that drive the most downstream impact for employee growth. Through Ivy, senior leaders and HR partners have a pulse on their org health by seeing insights and recommendations and the specific actions they can take to address risks, what blockers there are in team/org productivity, and how they can unblock them, and which managers need support and how they can coach those managers.

The Problem

When I joined the Global Talent Management team, HR products at Amazon were being built as one-off solutions to singular problems. Anecdotal evidence suggested that Amazon managers were overwhelmed by the administrative burden of talent management. HR processes were seen as a complicated and unclear, and every line of business had different standards and policies for processes that should be universal. The team had been created to try and address these problems, and had started building individual products to support promotions, compensation, career grown, onboarding, etc. Though these products were being built as new technology to solve specific use cases, they didn’t connect to each other in meaningful ways (e.g. a promotion would naturally result in a compensation change, but these two products didn’t work together) and Amazon employees had to remember distinct product names in order to take action (e.g. one had to remember what the promotion product was called in order to start the promotion process for an employee).

The Outcome

My design team (comprised of 10 UX designers, researchers, and writers) conducted generative research, multiple rounds of iterative design, and evaluative research to put forward the design strategy for Ivy, a new product that not only brought talent management products together into one interface, but surfaced the most important talent management information for Amazon managers and leaders, and taught Amazon’s unique culture at scale, through product. After the initial launch of Ivy, 91.7% of managers self-reported that Ivy tasks helped them prioritize the most important talent management actions. Customer feedback on the first launch was positive, ‘this has changed my life,’ and ‘I am so excited for this product.’

My Role

I lead the design organization through the design process of Ivy as the Head of UX and Design. I delegated key tasks to senior designers and researchers, wrote design strategy documents, lead collaborative design sessions, presented multiple iterations of the work at the senior executive level (Amazon’s ‘S-team’) and got my hands in the design and research directly as needed. Though Ivy was initially meant to bring only talent management products together, in the course of the two years my team spent working on it, it grew to become the one-stop-shop for HR at Amazon, when I moved on from the Ivy team, it was supporting over 70 internal products, and continuing to grow.

In the Ivy product, users can navigate by their team members to take specific actions for those people, and get organization level insights that help them understand how they are doing as leaders.

Detailed Case Study

The Problem

When I joined the Global Talent Management team, HR products at Amazon were being built as one-off solutions to singular problems. Anecdotal evidence suggested that Amazon managers were overwhelmed by the administrative burden of talent management at Amazon. HR processes were seen as a complicated and unclear, and every line of business had different standards and policies for processes that should be universal.

The concept of connecting experiences was born out of evaluative and generative research conducted by my team after I started in the role. Not only were the products we were shipping disconnected, the organization we were working in was operating in silo’s. It became clear we were placing the burdens of our organizational structure on our employees by shipping silo’d, one-off solutions to problems that were really connected. My team presented a research document that outlined where we believed we should focus over the next year:

Problem 1: Managers can’t identify the highest value actions. Managers need to identify, evaluate, and act on many actions to grow their talent. In a structured focus group study my team ran, users identified 396 unique actions managers were being asked to take in various products.

Problem 2: Managers spend too much time on low-value tasks. Managers were spending time trying to learn new talent products, in part due to needing to know how to navigate disparate products.

Problem 3: Managers don’t understand how talent processes are connected. Over 75% of managers indicated that they didn’t understand Amazon’s talent management philosophy or how Amazon’s talent management processes related to one another. Further, 45% of HR professionals at Amazon stated that they didn’t have flexibility within the products to support employees and managers in understanding and executing talent mechanisms.

The Solution

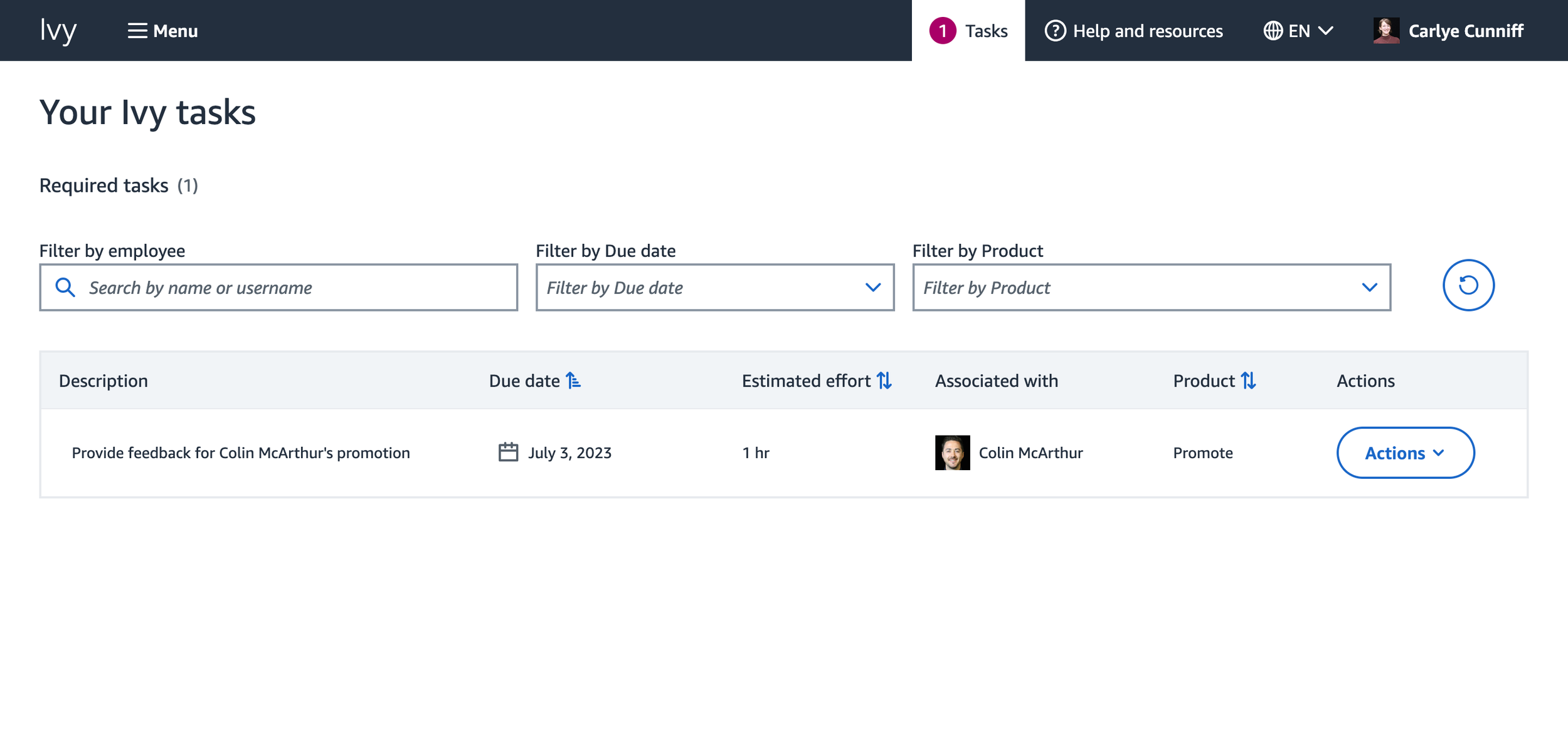

With clearer customer problems articulated and agreed on by leadership, my team was able to move on to more focused research and iterative design. The idea of a connected experience came forward quickly, but understanding what was most important in that connected experience was less obvious. I suggested that we run a Kano Model Study to both validate the teams qualitative findings and prioritize features to launch first. Our team delivered a list of features based on a combination of usefulness and frequency of use for managers. The first version of the Ivy product launched in 2019, with a global navigation that allowed users to switch easily between talent management products, a cross-product task center, which curated and prioritized tasks from across different products so managers could see everything they needed to do in one place, timelines for talent events, and an employee profile, so managers and HR professionals could see everything they needed to see about an employee in one place.

With the initial launch, we were able to validate our solution agains the problems we set out to solve.

Problem 1: Managers can’t identify the highest value actions. After launch, 91.7% of managers surveyed self-reported that Ivy tasks helped them prioritize the most important talent management actions.

Problem 2: Managers spend too much time on low-value tasks. Managers were spending time trying to learn new talent products, in part due to needing to know how to navigate disparate products. 41% of managers who indicated they spend too much time on talent processes said it was due to a counterintuitive product (see learnings section before for more information on this outcome).

Problem 3: Managers don’t understand how talent processes are connected. 15% of managers self-reported that they don’t understand Amazon’s talent management philosophy or how Amazon’s talent processes relate to one another, down from 75% before Ivy launched.

Design Strategy and Mental Models

As the Ivy project got underway, and our design cycles become more regular, I was able to step back from the day-to-day design and work on helping the organization understand and embrace the long term vision of the project. I was acting as a teacher and design evangelist, so that when the time came to step away from the role, the product would continue to be built from a human centered perspective. I relied heavily on mental models to help teach and align the organization to our strategy.

Mental Model 1 | The Product is The Process

The HR organization was entrenched in the idea that program managers should design the process, and that designers and product managers should then build a product to support their design. I frequently and vocally disagreed with this idea, and brought forward the concept that a poorly designed process would result in a poorly designed product. Over time, the team became more comfortable with the idea that design needed to be involved not only in how the product would function, but how the process and policy needed to be designed using the same human centered design concepts. This concept played out in the way we adjusted how we did change management (we used Ivy as the change management tool, rather than developing memos, emails, posters, in person trainings, etc), how the team worked (I implemented program design reviews before any pixels could be moved), and how leadership staffed the team (we moved from being heavily program management focused to hiring more product managers and designers). This shift eventually helped us make progress on the finding that the products in Ivy were counterintuitive.

Mental Model 2 | Flexibility within a Framework

I often used the analogy of the Amazon retail site to help explain the Ivy vision to the team. The Amazon home page is a framework that ensures a consistent customer experience while allowing for innovation and personalization in each individual component. Search, Browse and other navigational features follow consistent design principles to ensure customers can easily move around the site. Content on the Amazon retail page is personalized to specific customers based on their needs. Similarly, Ivy needed to become the framework that multiple products existed within. Ivy would provide the ‘UX layer’ in the form of guidelines, patterns, and real estate for teams to use, and the products with expertise in different customer journeys would build what they needed to build within that framework. In addition to the UX layer, I introduced the idea of ‘the engine room’ which were the individual products that came together to make the Ivy experience. Finally, I introduced the ‘service layer’ which were the pieces of the experiences that held everything together and made the product a cohesive experience; these were things like the design system being used, the notifications service that pulled information from multiple engines, and the global navigation. We didn’t want to rebuild the individual products, or create dependencies on individual teams, but rather create a system that allowed those individual products to work together for the customer.

Mental Model 3 | Organize by Journey

Something we heard over and over in our customer research was that our users didn’t know or care how the HR organization fit together, it was all HR to them. The fact that my team was responsible for the products about ‘talent management’ and a completely unrelated and separate team was responsible for distributing their paycheck did not matter. I relayed this critical tidbit of customer research constantly - so much so that in meetings people would often look at me and say it before I could. Knowing this, we were able to change both how we organized ourselves internally, and how we delivered information to our customers. We moved from a navigation of individual products to a navigation that focused on customer journeys. We also reorganized our leadership team into talent journeys, re-organizing so we were set up to deliver for customers in the way they navigated our programs.

Mental Model 4 | Navigate by People

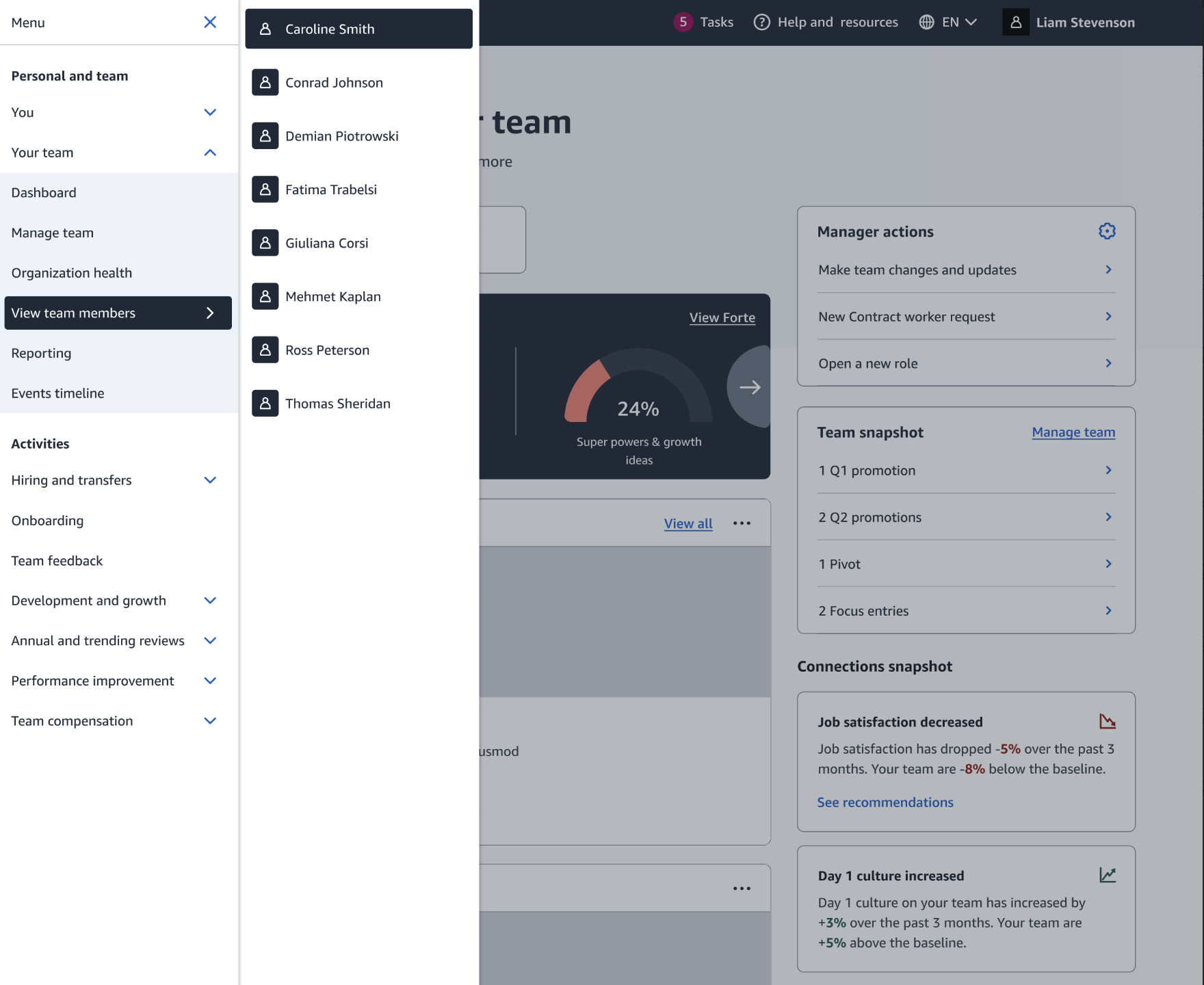

Another critical insight we gleaned from customer research was that the way people had to navigate our talent management products didn’t align with their mental models. Our customers expected to be able to navigate by people, rather than by process. As a manager, you would likely visit Ivy because you had a specific task in mind (e.g. person X is really excelling and is ready to start on their promotion path), they would expect to navigate to person X and take the right action for that person. Changing the information architecture of the Ivy system would also allow us to scale the system to include more and different types of products, and would eliminate duplicative UI elements (i.e. a list of employees that was present in each product’s landing page).

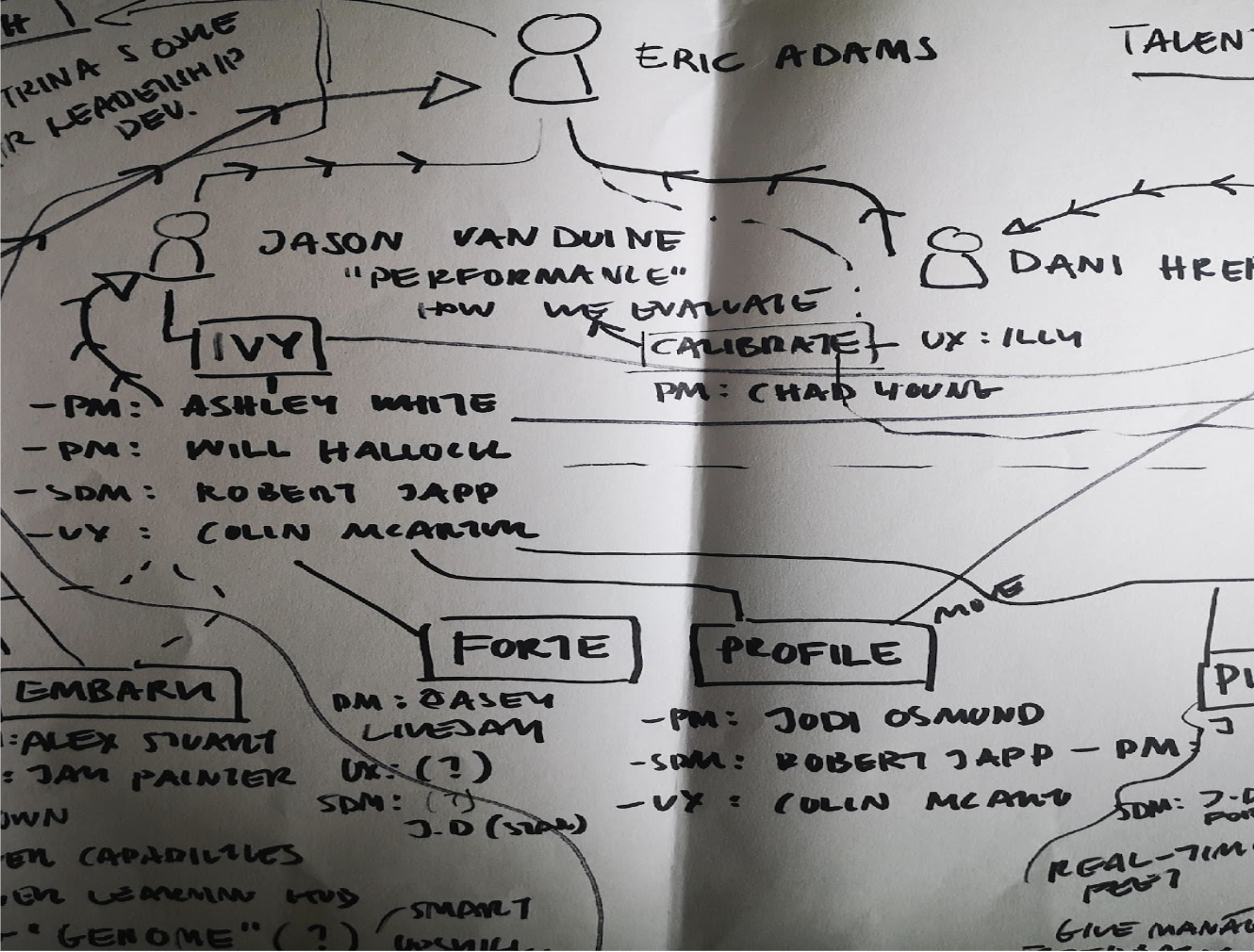

My team created a stakeholder map to understand and illustrate how the different parts of the organization fit together, and how the organizational structure wasn’t necessarily working for our customers.

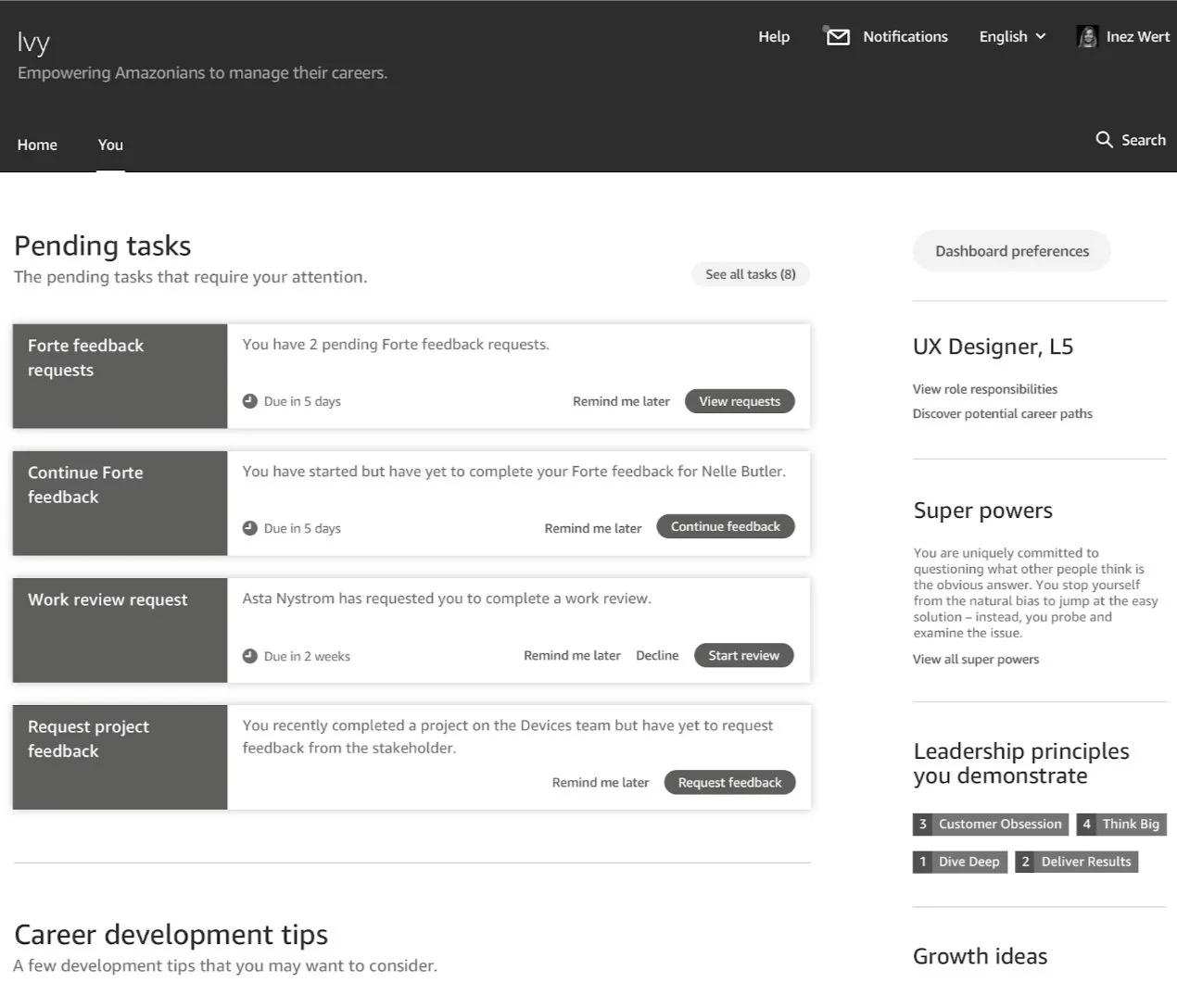

We learned that the most important feature to launch with first was tasks - helping managers prioritize all the possible things they could do for their teams in a day.

An early wireframe used for testing to better understand what was most important to launch first.

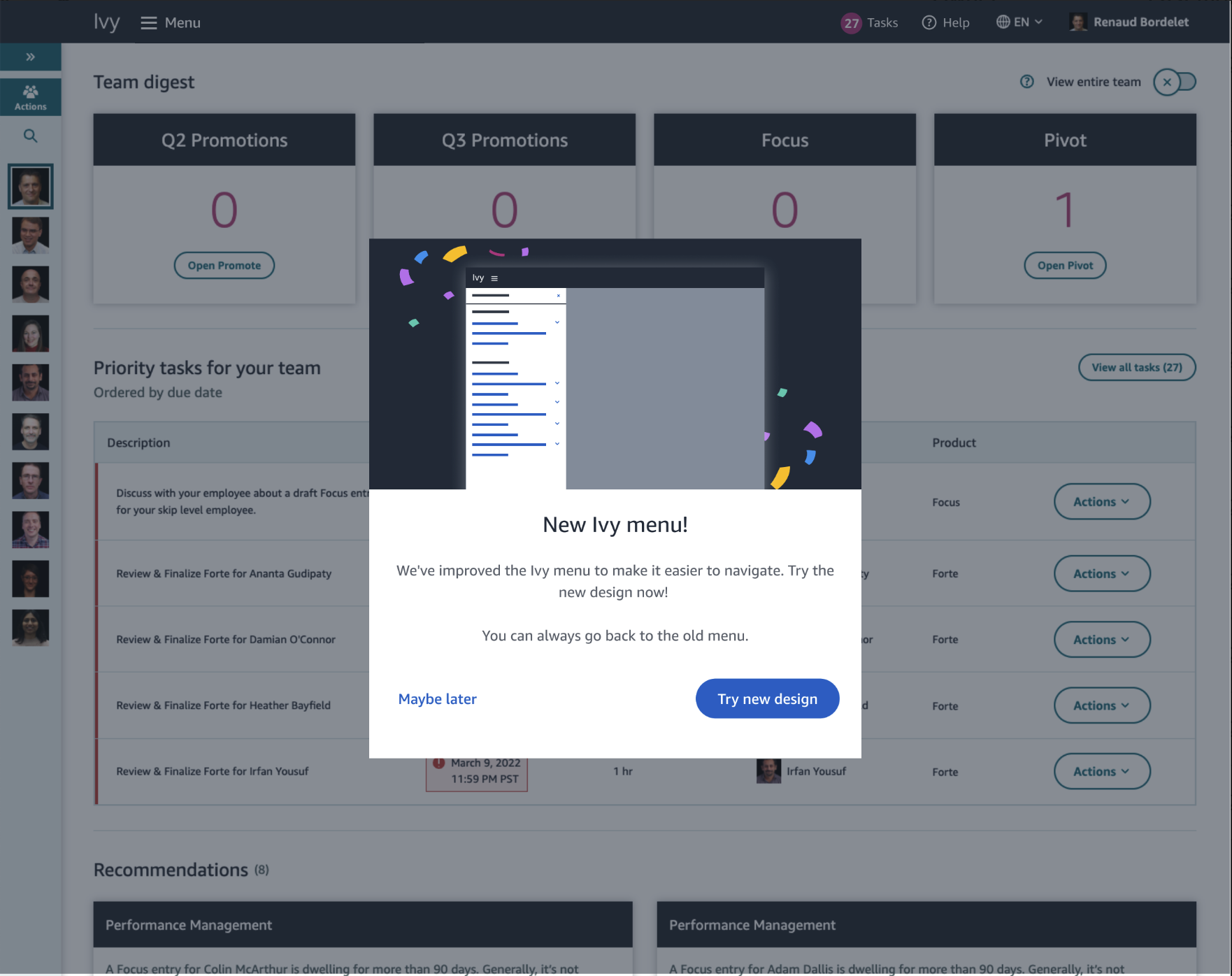

Modals were one strategy we used to introduce users to change in programs or processes.

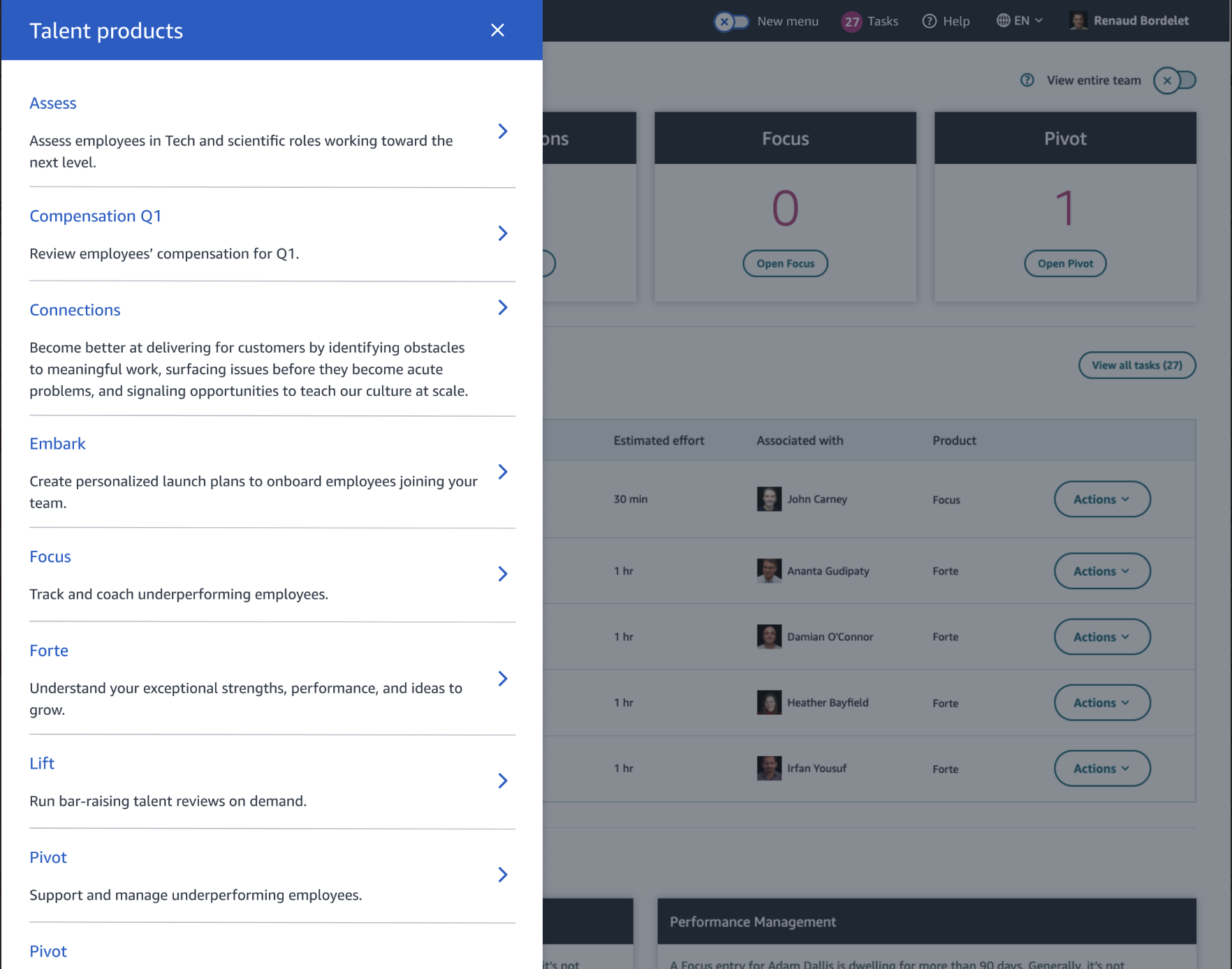

The Ivy product evolved from it’s first launch (navigation by products - above) to the mock up shown below, where a user can navigate by both their team members and specific journeys they may need to go through.